|

|

|

Interview with Mark Lehner, Archaeologist, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, and Harvard Semitic Museum

LEHNER: Wow, do you want the real answer or the abridged version? I first went to Egypt in 1972 as a tourist. And then I went back in 1973, the following year as a year abroad student at the American University in Cairo. And it's no secret that when I went I myself was imbued with the ideas of lost civilizations and inspired by a man named Edgar Cayce. So I was in fact, myself, looking for the lost civilization and something called the Hall of Records.

|

|

Hear Lehner via RealAudio: 14.4 | 28.8 | ISDN |

Or at least those ideas were on my mind. To make a long story short,

those ideas didn't stand up against bedrock reality. And so then I was still

fascinated by these pyramids and the Sphinx. Then I asked the question, well,

what is the real story? What is the story that the site itself has to tell.

And so that's what sustained me and kept me out there in a kind of exploratory

mode. NOVA: Why do we still have only limited knowledge about Giza and the construction of the pyramids there? And how do we know what we know about Giza?

|

|

Hear Lehner via RealAudio: 14.4 | 28.8 | ISDN |

LEHNER: Well, we know what we know from a few different kinds of information. We

have the architecture that's standing there. We have hundreds of tombs and

their superstructures and what we call their substructures, that is their

burial chambers and their shafts. We have the pyramids. We have the ruins of

the temples attached to the pyramids and the sphinx, of course. And so that's

kind of architectural. These tombs, many of them are inscribed with texts,

ancient hieroglyphic texts. Now it happens to be the case that in the time of

the pyramids, you don't have "The New York Times" in hieroglyphic. In fact,

you don't really have much narrative literature at all. But you have names.

You can deduce from these people's names and their titles, family

relationships. So we know where the tomb of Khufu's great granddaughter is,

for example. We know about the tomb of Khufu's mother, the Queen Mother, and

we know something about their occupations. Something about the way they

organized their society and what we would call their government. These titles

are fascinating. kind of architectural. These tombs, many of them are inscribed with texts,

ancient hieroglyphic texts. Now it happens to be the case that in the time of

the pyramids, you don't have "The New York Times" in hieroglyphic. In fact,

you don't really have much narrative literature at all. But you have names.

You can deduce from these people's names and their titles, family

relationships. So we know where the tomb of Khufu's great granddaughter is,

for example. We know about the tomb of Khufu's mother, the Queen Mother, and

we know something about their occupations. Something about the way they

organized their society and what we would call their government. These titles

are fascinating.

So we have texts, we have architecture, and then what we're trying to catch up

with at Giza is the third category of information that hasn't been plumbed as

much as texts and tombs and temples. And that is archaeological information:

mud, debris, fish bones, ancient bakeries, not the architecture that they built

NOVA: How do you know what the heiroglyphic texts are saying? LEHNER: Well, it's hard. We get this question quite a lot actually. How do we know what the texts are saying? Because we know how to read hieroglyphics. We've been to hieroglyphics class. NOVA: What is hieroglyphics class?

|

|

Hear Lehner via RealAudio: 14.4 | 28.8 | ISDN |

LEHNER: In hieroglyphics class you're basically learning a foreign language.

I mean we all know what it's like to learn French or to learn German. But when

you consider learning Chinese or Japanese or Arabic for Europeans and

Americans, you're not only learning a different language, but you're learning a

different script. Now consider that you're learning a different script and a

different language that's been separated from us by a good 2000, 2500 years.

That is it's been dead, unspoken for that long. And then consider this

language didn't last a millennium, a thousand years, but rather 3,000 years and

went through many different changes. So basically what you're asking is how do

you learn to read Egyptian, and that is becoming an Egyptologist. And in order

to become an Egyptologist, you go through a training process where you learn

old Egyptian from the time of the Pyramids, middle Egyptian from the time of

the classic literature of ancient Egypt, new Egyptian which is a later version,

and you learn something like five different scripts. You learn hieroglyphic,

you learn hieratic, which is like shorthand hieroglyphics, you learn demotic,

which is more literally like shorthand, like a stenographer's shorthand of

hieroglyphic. You learn Coptic, which is the ancient Egyptian language written

in the Greek alphabet. Now there are great debates about how to read these

texts. But for the laymen, these debates are really angels dancing on the head

of a pin. Egyptologists are not in great disagreement about the general gist

of what the texts are saying. So there is a fair amount of consensus about how

the texts are read. language didn't last a millennium, a thousand years, but rather 3,000 years and

went through many different changes. So basically what you're asking is how do

you learn to read Egyptian, and that is becoming an Egyptologist. And in order

to become an Egyptologist, you go through a training process where you learn

old Egyptian from the time of the Pyramids, middle Egyptian from the time of

the classic literature of ancient Egypt, new Egyptian which is a later version,

and you learn something like five different scripts. You learn hieroglyphic,

you learn hieratic, which is like shorthand hieroglyphics, you learn demotic,

which is more literally like shorthand, like a stenographer's shorthand of

hieroglyphic. You learn Coptic, which is the ancient Egyptian language written

in the Greek alphabet. Now there are great debates about how to read these

texts. But for the laymen, these debates are really angels dancing on the head

of a pin. Egyptologists are not in great disagreement about the general gist

of what the texts are saying. So there is a fair amount of consensus about how

the texts are read. NOVA: How do you know how the words were pronounced? LEHNER: Pronouncing is a different thing altogether, because the Egyptians, like modern Arabic to some extent, wrote mainly the consonants and not the vowels. So the vocalization is something that's very difficult. As a matter of fact, it's an ongoing field of study -- just how did they pronounce these words. And certainly it changed considerably over the entire 3,000 years that Egyptian was spoken. I mean some people may know the difference between the language that we speak today, the English that we speak at least here in America, especially, and that that was spoken by Chaucer in Chaucer's time some 800 years ago. Consider differences that are at least double that at least in terms of the length of time. We're on safer ground in the Coptic period, starting from about the 1st to 4th centuries A.D., because with the writing of the Egyptian language at that stage in the Greek alphabet now we have an idea of pronunciation. But how they actually pronounced these words is very difficult. So we commonly put e's in everything. So you have the word PRT which means seed or it means to come forth. Egyptologists by convention throw in e's, "peret." NOVA: As an archaeologist, how do you know where to begin digging, especially at a location as vast as the Giza Plateau, and will there continue to be new things to look for in piecing together the story of Old Kingdom Egypt?

NOVA: What patterns have you found across the landscape of Giza?

LEHNER: The stone that the pyramids are founded on is a hard stone composed of

an extinct fossil called nummulites, a word that derives from the Latin word

for coin, because they look like small disk shaped coins. If you stand at the

foot of the Great Pyramid on the east side and look down at the rock at your

feet, you'll see it is nothing but compact nummulites. Fifty million years ago

when the seawaters of the Eocene period covered Egypt, northeast Africa, they

began laying down sediments that became the limestone table land of Egypt.

NOVA: Tell us about your extensive mapping of the Giza Plateau.

|

|

Hear Lehner via RealAudio: 14.4 | 28.8 | ISDN |

LEHNER: My work started with the Sphinx, and we did this five-year project to

document the Sphinx. And the Sphinx is a natural cross section of the natural

geology at Giza. And I realized that the layering in the Sphinx had a lot to

say about the layering in the Giza Plateau as a whole. And that means that the

Sphinx gives us clues as to the layers that the Egyptians exploited for

building the pyramids, because they're of different qualities and so on. So

then I started looking for the quarries. The Sphinx is kind of a quarry, you

know, it's made out of the natural rock. Where is the main quarry for Khufu?

And where is the main quarry for the Khafre Pyramid? And that led me to a kind

of geological approach to the whole plateau. The pyramids are so big that the

evidence of how they were built must have left disturbance to the landscape on

a geological scale. So that's why we started the Giza Plateau mapping project

in 1984. And in fact, we went on and put in survey control over the entire

plateau. So that now, with surveying instruments, we know where we are to an

accuracy of a millimeter, with laser or infrared distance measures and

theodolites, anywhere on the plateau. And we go directly from that into the

computer and we produce this computer model.

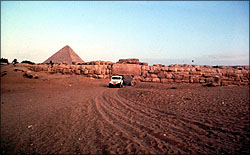

NOVA: Your bakeries excavation lies to the south of the Wall of the Crow. What can you tell us about the Wall of the Crow?

LEHNER: The Wall of the Crow itself is a fascinating structure, somewhat

enigmatic, more than two football fields in length. If it were anywhere here

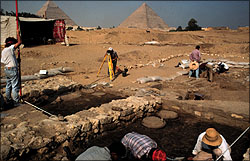

NOVA: As you're excavating the ancient bakeries, for example, what does the architecture look like as you dig down through the mud from above?

LEHNER: As we dig, we sieve great quantities of our dirt to take out the

smallest bits of material evidence -- bones, microfauna of birds, fish, rodents,

small bits of pottery. Wilma Wederstrom, a paleobotanist from the Harvard

Botanical Museum, takes a great deal of our dirt here from our ancient bakeries

and puts it through a barrel which has been modified to be a flotation machine.

(5) Mark Lehner; (8) John Broughton; (11) Carl Andrews

Contents | Mail

|

NOVA: Can you briefly tell us about your history at Giza and tell us about

some of the work you've done there? In essence, why Giza?

NOVA: Can you briefly tell us about your history at Giza and tell us about

some of the work you've done there? In essence, why Giza? in stone, but the architecture that they built out of the mud of the valley

floor which is in fact where they lived. And so there's a whole counterpart to

the pyramids, which are lost, like a kind of a City of the Dead. Not a lost

city, but a City of the Dead that we know, whose ruins still stand. Zahi

(Hawass) and I are to some extent looking for the lost city of the pyramids.

The city that we don't see. The city whose ruins are made out of mud brick,

stone rubble. The bakeries, the breweries, the sandal makers, and all the

different things that sustained the building of the pyramids and the everyday

life of the people who built them.

in stone, but the architecture that they built out of the mud of the valley

floor which is in fact where they lived. And so there's a whole counterpart to

the pyramids, which are lost, like a kind of a City of the Dead. Not a lost

city, but a City of the Dead that we know, whose ruins still stand. Zahi

(Hawass) and I are to some extent looking for the lost city of the pyramids.

The city that we don't see. The city whose ruins are made out of mud brick,

stone rubble. The bakeries, the breweries, the sandal makers, and all the

different things that sustained the building of the pyramids and the everyday

life of the people who built them. LEHNER: What there is to look for is the soft tissue of ancient society for

which these stone monuments are simply the petrified remains of the

preparations they made for the journey into the afterlife. The soft tissue

would be the housing, the infrastructure, the socio-economic forces. And what

led us to look where we're looking was to some extent the layout of the whole

plateau and the patterns that we see across the landscape.

LEHNER: What there is to look for is the soft tissue of ancient society for

which these stone monuments are simply the petrified remains of the

preparations they made for the journey into the afterlife. The soft tissue

would be the housing, the infrastructure, the socio-economic forces. And what

led us to look where we're looking was to some extent the layout of the whole

plateau and the patterns that we see across the landscape.  Through the Eocene period the waters gradually began to retreat northwards to

what is now the Mediterranean Sea. And 50 million years ago the headwaters of

this retreating sea were right about where the Giza Plateau is. This nummolite

embankment was laid down from northeast to southwest in the northwest part of

the Giza Plateau, and it became a very hard foundation that eons later the

pyramid builders would use as a good support, a good base for their pyramids.

However, the part of the plateau downslope to the southeast in the direction

where we're digging, south of the Wall of the Crow, the stone downslope in that

direction was actually formed as the seawaters were retreating, and that

nummolite embankment came almost to the surface. So the south, southeast part

of the Giza Plateau, for example where we now find the Sphinx, was a kind of

backwater lagoon, 50 million years ago. And it laid down softer silts and

sediments that became the layers you see in the body and head of the Great

Through the Eocene period the waters gradually began to retreat northwards to

what is now the Mediterranean Sea. And 50 million years ago the headwaters of

this retreating sea were right about where the Giza Plateau is. This nummolite

embankment was laid down from northeast to southwest in the northwest part of

the Giza Plateau, and it became a very hard foundation that eons later the

pyramid builders would use as a good support, a good base for their pyramids.

However, the part of the plateau downslope to the southeast in the direction

where we're digging, south of the Wall of the Crow, the stone downslope in that

direction was actually formed as the seawaters were retreating, and that

nummolite embankment came almost to the surface. So the south, southeast part

of the Giza Plateau, for example where we now find the Sphinx, was a kind of

backwater lagoon, 50 million years ago. And it laid down softer silts and

sediments that became the layers you see in the body and head of the Great

Sphinx. As you see in the body of the Sphinx, in the chest for example, these

layers tend to alternate, soft, hard, soft, hard. And so they present a very

good opportunity for extracting blocks by cutting along the soft layers and

taking the stone out in the intervening harder layers. So downslope from the

pyramids from that great diagonal, you find most of the quarries for the three

great pyramid projects.

Sphinx. As you see in the body of the Sphinx, in the chest for example, these

layers tend to alternate, soft, hard, soft, hard. And so they present a very

good opportunity for extracting blocks by cutting along the soft layers and

taking the stone out in the intervening harder layers. So downslope from the

pyramids from that great diagonal, you find most of the quarries for the three

great pyramid projects.  in the United States they'd build a National Park around it. During our 1991

season we would drive our jeep right under the huge gable, the huge gateway in

the center of the wall. In our '91 season we did excavations right at the very

foot of the wall, and the wall, of course, gives a panoramic view of all three

Giza Pyramids looking from the southeast to the northwest. The wall is a good

ten meters, or 30 feet high, which means that gateway through which we drove

our jeep is 21 feet or 7 meters high, making it one of the largest gates maybe

in the ancient world. Ancient Egyptians usually don't make such massive walls

and colossal gates without there being a very powerful reason for it. And it

causes us to wonder even more, what lay to the south.

in the United States they'd build a National Park around it. During our 1991

season we would drive our jeep right under the huge gable, the huge gateway in

the center of the wall. In our '91 season we did excavations right at the very

foot of the wall, and the wall, of course, gives a panoramic view of all three

Giza Pyramids looking from the southeast to the northwest. The wall is a good

ten meters, or 30 feet high, which means that gateway through which we drove

our jeep is 21 feet or 7 meters high, making it one of the largest gates maybe

in the ancient world. Ancient Egyptians usually don't make such massive walls

and colossal gates without there being a very powerful reason for it. And it

causes us to wonder even more, what lay to the south.  LEHNER: It's a far more difficult process than finding stone tombs, temples,

and pyramids, because mud buildings disintegrate and bury themselves in the mud

from which they are composed.....By carefully scraping and eking out wall lines, you begin to allow the architecture to emerge from the

dust of its own ruins. And by working on this over the course of several weeks

we were able to eke out the whole building.

LEHNER: It's a far more difficult process than finding stone tombs, temples,

and pyramids, because mud buildings disintegrate and bury themselves in the mud

from which they are composed.....By carefully scraping and eking out wall lines, you begin to allow the architecture to emerge from the

dust of its own ruins. And by working on this over the course of several weeks

we were able to eke out the whole building.  NOVA: Can you tell us a little about the process in an archaeological dig?

NOVA: Can you tell us a little about the process in an archaeological dig? The dirt sinks down through the water and through mesh of different grades,

starting with mesh about a half an inch to a quarter of an inch, going down to

mesh the size of the screen on a screen window, and finally through

cheesecloth. And in the cheesecloth Wilma collects everything that is

preserved through the water, through the flotation because it's been

carbonized. And it looks like black muck. She dries that out and she then

takes the dirt, or the floated carbon residue, and she puts it on little petri

dishes, and with the patience of Job goes through it with little tweezers and

picks and identifies field weeds, ancient grains and so on, which give us an

index to the climate, the diet, and all kinds of information about the ancient

conditions, when these buildings were in the prime of their life.

The dirt sinks down through the water and through mesh of different grades,

starting with mesh about a half an inch to a quarter of an inch, going down to

mesh the size of the screen on a screen window, and finally through

cheesecloth. And in the cheesecloth Wilma collects everything that is

preserved through the water, through the flotation because it's been

carbonized. And it looks like black muck. She dries that out and she then

takes the dirt, or the floated carbon residue, and she puts it on little petri

dishes, and with the patience of Job goes through it with little tweezers and

picks and identifies field weeds, ancient grains and so on, which give us an

index to the climate, the diet, and all kinds of information about the ancient

conditions, when these buildings were in the prime of their life.